“Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you”. It sounds so pious, so noble, so beautiful, doesn’t it? It’s the perfect verse for sermons and devotionals, and it’s such an easy verse to say. But it’s also an easy verse to vanish in our hearts and minds when we see the next national news headline, or when we scroll through the comments of a politically charged post, or when we drive on the highway and we have to slam on our breaks for that person who seems to be actively seeking to kill people.

And what about if someone took an axe and murdered your innocent friend for no good reason? Could you love them then? Would you feel nothing but moral outrage towards this murderer, or would you be able to make room for compassion and mercy? How can you balance justice and love? These are all important questions that Fyodor Dostoyevsky explores in his moving novel Crime and Punishment, particularly through the characters of Raskolnikov (a young, poor, former university student, and the novel’s protagonist), who is the murderer, and Sonya (a prostitute Raskolnikov befriends), who is the bereaved.

Double Murder

Raskolnikov originally plans to murder only one person: an old, rich pawnbroker named Alyona Ivanovna. He plans to kill and rob her, and he tries to justify this action to himself. Alyona is not a very nice woman, and besides, her money could be used for good. Motivated (at least superficially) by this logic, Raskolnikov executes his plan.

Raskolnikov thinks that Alyona will be alone when he carries out the murder. But his plan goes horribly wrong when Lizaveta, Alyona’s younger half-sister, steps into the room after Raskolnikov has just murdered Alyona. Raskolnikov rushes at Lizaveta with an axe, and her reaction is heartbreaking:

“And this wretched Lizaveta was so simple, so downtrodden, and so permanently frightened that she did not even raise a hand to protect her face, though it would have been the most necessary and natural gesture at that moment, because the axe was raised directly over her face”.1

Now it turns out that Sonya was friends with Lizaveta, and they used to read the Bible and talk together. So after Raskolnikov confesses to Sonya that he murdered Alyona and Lizaveta, he does a whole song and dance to try to justify his actions to her. He tries to compare himself to “Napoleon”, an “extraordinary man”, who has to get his hands dirty in order to get his career going for the greater good of mankind. He then tries to say that he planned on robbing Alyona in order to support himself as a university student so he could help his family. But eventually he reveals the horrible truth:

“I wanted to kill without casuistry, Sonya, to kill for myself, for myself alone! I didn’t want to lie about it even to myself! It was not to help my mother that I killed-nonsense! I did not kill so that, having obtained means and power, I could become a benefactor of mankind. Nonsense! I simply killed-killed for myself, for myself alone-and whether I would later become anyone’s benefactor, or would spend my life like a spider, catching everyone in my web and sucking the life-sap out of everyone, should at that moment have made no difference to me!”2

So Raskolnikov is a moral monster who planned to kill for purely selfish reasons, and poor Lizaveta was caught in the crossfires of his wicked scheme. Now even though Raskolnikov had done something incredibly kind to her before this, giving her all his money so she could support her family, it was perfectly understandable for Sonya to despise him at this moment. Past charity does not excuse a malicious double murder. She had every reason to call the police and let justice be done and leave the matter at that. But her reaction is very interesting and morally nuanced.

Toxic Empathy or Sinful Wrath?

What does it mean to “love thy enemies”? What exactly does Christian love and empathy entail? It’s easy to manipulate verses like this one, and so just as we roll our eyes when someone misuses the verse “Judge not…”, we might also be tempted to have a similar reaction when someone says “love thy enemies”.

We might insist that Christ’s teachings about love are all well and fine, but they do not mean we abandon justice, which God has also commanded us to pursue (Micah 6:8). Justice demands law and order, and the punishment of evil. And some other Christian may push back on that, and insist that God’s commands about justice are all well and fine, but we must act lovingly first. Love demands compassion and mercy towards evildoers and criminals.

And of course, when we have a tension like this one, it is easy to abandon all nuance and slip into extremes. So Christian X may say, “sure, Raskolnikov committed ‘murder’, but he’s had a tough life, and he’s a hypochondriac, and he’s done some nice things before, and besides, Alyona wasn’t so innocent herself, so who am I to judge…”. And Christian Y may say, “Raskolnikov is the spawn of Satan, who butchered two innocent women for selfish reasons, and he deserves a slow, agonizing death, and I would do it myself if I could …”.

What is the temptation of our day? Is it to let criminals get away with murder in the name of love and empathy? Or is it to strip these wrongdoers of all humanity and deny them any sort of compassion in the spirit of moral wrath? Which extreme will we choose? Or can we balance justice and love?

Sonya’s Saintliness

Sonya does. When Raskolnikov asks her what he should do now, this is what she says:

“Go now, this minute, stand in the crossroads, bow down, and first kiss the earth you’ve defiled, then bow to the whole world, on all four sides, and say aloud to everyone: ‘I have killed!’ Then God will send you life again.”3

Raskolnikov understands what this sort of public confession entails. It is the justice he has been dreading the whole novel. It means he will go to prison. He says:

“So it’s hard labor, is it, Sonya? I must go and denounce myself?”

And she responds:

“Accept suffering and redeem yourself by it, that’s what you must do.”4

So Sonya does not throw justice out in the name of love. She demands justice for the murders of Alyona and Lizaveta. But she also does not throw out love in the name of wrath. Instead, she offers Raskolnikov her life. Sonya wants both Raskolnikov and herself to wear cross necklaces as they both go to suffer “hard labor”:

“Here, take this cypress one. I have another, a brass one, Lizaveta’s. Lizaveta and I exchanged crosses; she gave me her cross, and I gave her my little icon. I’ll wear Lizaveta’s now, and you can have this one. Take it … it’s mine! It’s mine!” she insisted. “We’ll go to suffer together, and we’ll bear the cross together!”5

And she does. She follows him to the police station where he confesses his crime. And after he is sentenced to a prison camp in Siberia, she follows him there, starts a correspondence with his family so he can receive news from them, and frequently visits him in the prison. And even after all of this, he mistreats her and acts rudely to her. But she persists in her compassion, and eventually Raskolnikov repents, becomes a changed man, and comes to love her.

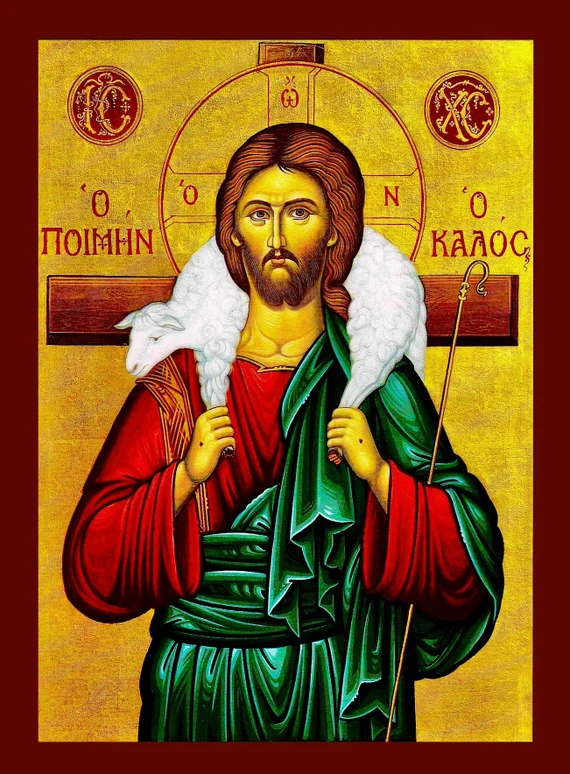

Behold the Lamb of God

When we witness injustice, whether done to us or others, it is easy to rage, and treat the evildoer the same way Raskolnikov’s fellow prisoners treat him:

“You’re godless! You don’t believe in God!” they shouted. “You ought to be killed!”6

But it’s infinitely more difficult to treat the evildoer with the Christlike love and mercy that Sonya exemplifies. Now obviously, we are not obligated to follow our enemies all the way to labor camps like Sonya does. But we are commanded to love them, and pray for them, and forgive them seventy times seven. As Sonya shows, this love need not come at the expense of the just condemnation and punishment of evil. But it does come at the expense of our desire to hate those who have wronged us.

It is interesting that the prisoners, who are murderers just like Raskolnikov, declare that he “ought to be killed.” In God’s eyes, before we accepted Christ, we were all murderers, all sinners who rebelled against God and who had no right to condemn anyone (see Matthew 18:21-35, the parable of the unmerciful servant, for Jesus’s teaching on this). But despite our sin and hypocrisy, it is Christ who bears our cross and suffers hard labor in our place and resurrects us. It is this Christian love that Dostoyevsky beautifully illustrates in his novel, and it is (one reason) why I personally believe that Crime and Punishment is one of the greatest Christian novels of all time.